First I gotta do all the lectures I missed. I’ll be going in reverse order

SOLID design

- Makes code reusable, portable, easy to extend and modify!

Single responsibility Principle Open/Closed principle Liskov’s substitution principle Interface Segregation principle Dependency inversion principle

SRP

- A class should only have “1” reason to change

- If a class has “more than 1 motive for changing a class” then it has “more than 1 responsibility”

- Example: Changing the width of a book shouldn’t change it’s box size. PhysicalBook isn’t all about “determining the box size of a book”. Instead it’s responsibility is “representing a physical book object”

- Another responsibility would be “representing the size of a physical book”. That’s is what is meant by SINGLE responsibility!

- You can delegate these responsibilities outside of the class, so long as it decouples things.

- If a class has “more than 1 motive for changing a class” then it has “more than 1 responsibility”

public class PhysicalBook extends Book implements Packagable {

Dimensions dimensions;

@Override

public Dimensions getDimensions() {

return dimensions;

}

public PhysicalBook(String isbn, String title, double length, double width, double height) {

super(isbn, title);

dimensions = new Dimensions(length, width, height);

}

@Override

public String determineBoxSize() {

double length = dimensions.getLength();

double width = dimensions.getWidth();

double height = dimensions.getHeight();

double max = length;

if (max < width)

max = width;

if (max < height)

max = height;

if (max < 5)

return "small";

else if (max < 15)

return "medium";

else

return "large";

}

}

}- This violates SRP because there are two responsibilities. One is representing a “physical book” and the other is “determining its box size”. in reality, the box size thing should be done somewhere else.

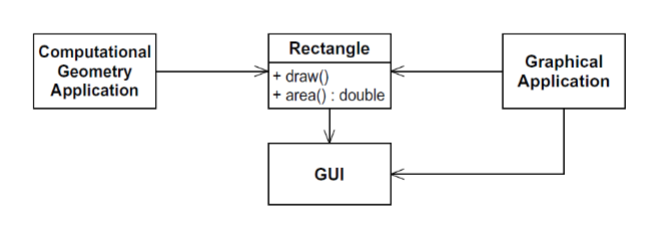

- Another example. Note how two classes require the rectangle for different reasons, and the rectangle is responsible for those two reasons (“drawing” for the graphical app, and “area” for the computation app)

OCP

- Open/Closed principle

- ”Open for extension, closed for modification”

- A class can be extended just fine, so long as it doesn’t modify the parent classes behaviour

- If you want to add a new feature, you should only create new code. If you have to change code that causes a cascading effect, that is BAD. Very “rigid”

- This comes from abstractions that are “fixed” yet represent infinite possible behaviors.

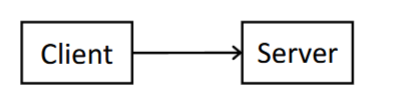

- Both of these classes are concrete, and the client uses the server. If I change the server, the client may also change. The client has a direct dependency of the “Server”

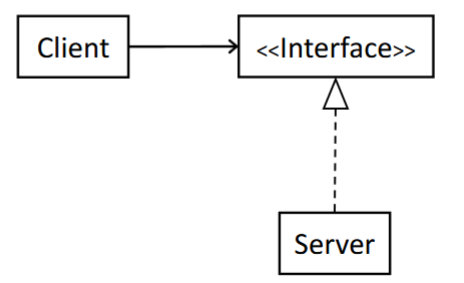

- Instead make client rely on an interface that we define (this is the “adding code” thing we were talking about). It requires just enough info that the client needs. All you do now is make server implement the interface, and pass the interface into the client. If the client wants to use another implementation, you swap it out easy peasy. If you want to change the client, you don’t change either the Client nor the Server’s code. You change main to use a new class you define later.

Liskov’s Substitution Principle (LSP)

Subtypes must be substitutable for their base types!

- For all properties of the parent, it should be the same with the child.

- “If it looks like a duck, quacks like a duck, but needs batteries, it doesn’t satisfy LSP”

- Because the robot duck cannot replace “duck” in every scenario. It might not “quack” the same times the regular duck does (think about the batteries running out!)

- Because the robot duck cannot replace “duck” in every scenario. It might not “quack” the same times the regular duck does (think about the batteries running out!)

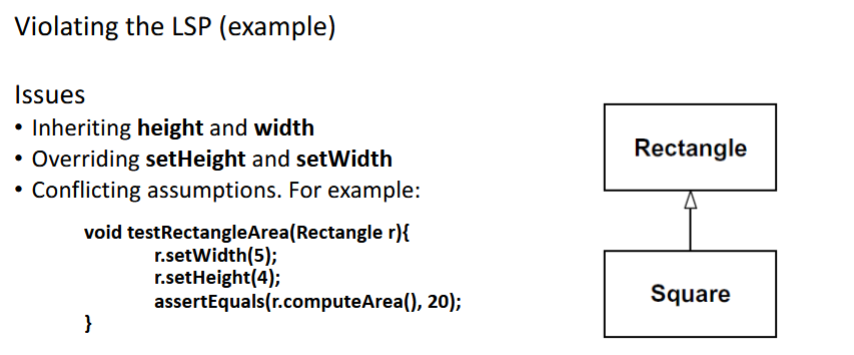

- A rectangle as a length and width. A square implementing a rectangle means it overrides the “area” such that it just outputs height * height. it overrides setHeight and setWidth!

- “in isolation, code might look fine. Only in practice, or relative to how the client uses your code, does it fall apart”

[!quote ] This point emphasizes that good design isn’t just about what the code does; it’s about what the code promises to do. The programmer writing the client code makes assumptions based on the class’s name, methods, and the overall context. A well-designed class honors those assumptions. A poorly designed class, even if it works in some cases, will break when a client makes a “reasonable” but unfulfilled assumption

ISP (interface segregation principle)

- Only for interfaces

- Clients should not be forced to depend on methods THEY DON’T USE!

- Deals with interfaces who aren’t cohesive. (i.e. the interface does more things than it should. Needs to be broken up!)

- If i have an enemy with an interface that returns a point to pathfind to, and a way to take damage, that’s great. But if I have a rock as an entity, I would have to use this same interface even though it can’t pathfind (redundant!). Instead I would split into two interfaces, compose 1 “Enemy” interface with the other 2 interfaces, and use that! Solution to ISP: Create sub-interfaces. Compose into big interface

DIP: Dependency-Inversion Principle

- High-level things should not rely on low-level things. Both should depend on abstraction. OR

- Details depend on abstractions, but abstractions should not depend on details.

- If i want an enemy that moves, the details will depend on those criteria, and execute them though a black-boxed web.

- High-level stuff should be independent of stuff that contains implementation details.

- Without DIP, it becomes hard to reuse high-level stuff (too many small things to remember about when using!)

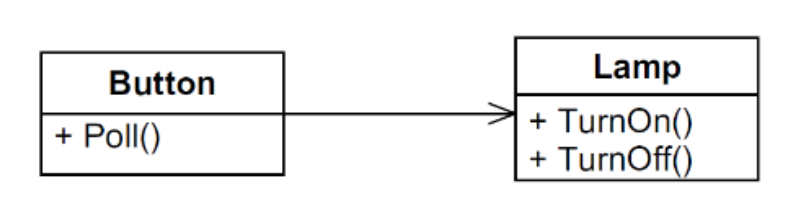

- Button → Lamp = button relies on lamp

- Is this SRP? Well, the single responsibility of the lamp seems to be controlling “on” and “off”-ness

- Is it OCP? Well yes, it does! If the button polls a different way, the lamp would change. If the lamp wants to use, idk, a timer instead of a button, it would be hard to change that. Have an interface for turn on / turn off. Anything can deal w/ it then

- Liskov’s? Well there is no abstractions

- ISP? No interfaces here

- DIP? Well the “button” (high-level) relies on the lamp (low-level). As such, the “button” should rely on an abstraction instead.

- Solution: Make button rely on an interface (takes it in as a constructor arg, for instance). Make lamp implement it. Button can call turn on or turn off, which will do so for the lamp.

Design Patterns

- There are structural, behavioral, and creational patterns

- For creational (deals with constructing) we have singleton and factory

- For structural (design of code) we have adapter and facade

- For behavioral (does certain things) we have observer and strategy patterns

Singleton

final class Singleton {

private static Singleton instance;

private Singleton() { }

public static Singleton getInstance() {

if (instance == NULL) instance = new Singleton();

return instance;

}

}Factory

- Makes a class create objects for you instead, while having other business logic while constructing

- The “creation” is implemented by child factory classes,

class Item()

{

/// stuff

}

abstract class Factory()

{

// Not called elsewhere. Only called by "addItem"

public abstract Item factoryMethod();

List<Item> allItems;

public Item addItem() {

Item newItem = factoryMethod();

allItems.add(newItem);

return newItem;

}

}

public class ConcreteItemCreator extends Factory

{

@Override

public Item factoryMethod()

{

return new FancyItem();

}

}Concrete Product = Fancy Item Product = Item Concrete Creator = Declares how to instance Fancy Item Abstract Creator = Defines what a creator looks like, what items it takes. Any time we call “addItem” it will create a list of that item type. So convenient!

- No, this doesn’t create a global list of items. That is for another day.

Facade (structural)

Have 1 class that abstracts many many other classes. Then the client can interface with this Facade.

public class Pathfinder

{

public Point getNextPoint();

public void addForceToPoint(Point point);

}

public class HealthComponent

{

public int getHealth();

}

public class MovementComponent {

public void addForceToPoint(Point point);

}

public class Enemy()

{

Pathfinder pathfinder;

HealthComponent healthComponent;

MovementComponent movementComponent;

public void die()

{

System.out.println("i am die");

}

public void update()

{

Point point = pathfinder.getNextPoint();

movementComponent.addForceToPoint(point);

if (healthComponent.getHealth() < 0) die();

}

}

public class CustomEnemy()

{

Enemy enemyAi;

public void update()

{

enemyAi.update();

}

}- This is a facade! The custom enemy has nothing to worry about. The “enemy” abstracts the complexities

Adapter

Lets classes that have nothing to do with another behavior, but have an implementation you like, work together without mutating code!

The client really wants to us a specificRequest from the class we want to adapt — the “adaptee”. It requires a “target” interface to provide the implementation. Now, we need to bridge the gap from the interface and the adaptee. It’s as simple as creating a new concrete class, implementing the interface (so the client can use it) by using the implementation of the Adaptee class.

So it’s as easy as: create new concrete class, implement, use adaptee.

Observer my beloved!

- Lets functions from other classes be signaled when a certain thing happens.

- More formally: “A one-to-many dependency between objects. When one object stages state, its dependents are notified and updated"

"Observer” is an abstract class / interface that dictates the common “notification method” that these observers will run via the “Subject”. The subject is the thing all the observers are looking at. It can be concrete, keeps track of many “Observers” and when the time is right, it goes through all of them and calls “the notification method”. All concrete observers implement “observer”.

You can go a step further and make “subject” implement an interface “subject” such that you can have many subjects with its own observers, too.

Strategy (behavioral)

- Make a family of algorithms that implement 1 “format” (via interface)

- Then your code can use this 1 interface to dynamically switch between many versions of the algorithm

interface DateFormatStrategy {

public String format(int day, int month, int year);

}

public DMYFormat implements DateFormatStrategy {

public String format(int day, int month, int year) {

return day + "/" + month + "/" + year;

}

}

public void main()

{

DateFormatStrategy strat = new DMYFormat();

strat.format(12, 2, 2004); // Uses DMY format!

}

Clean Code

Modularity

- Low coupling. High cohesion!

Coupling

- The entanglement of two different modules. ✨Interdependence ✨

- Makes code harder to understand

- to test

- to fix errors

- changing1 thing changes other things

- Ways to fix

- Dependency Inversion Principle (high level doesn’t worry about low-level. If so, abstract)

- Composition > Inheritance

- Proper encapsulation

- Law of Demeter

Cohesion

- Degree of interconnectedness!

- Low is good. Understandable, less errors, reusable, changes have no side effects.

- How to do? Confirm to SRP!

Clean classes

- Should be small

- Should be cohesive (small # of instance vars)

Clean Functions

- Func should also be small!

- if, else, while statements shouldn’t be more than 1 line (otherwise break up)

- Funcs do “1” thing only!

- They have only

1level of abstraction- Means all func calls inside a func should be roughly on the same level of abstraction.

- Long names are good as long as they’re informative

- Less args is better

- Meaningful names!

- Classes are nouns, methods are verbs. 1 word per concept.

- i.e. don’t have fetch, retrieve, get as equivalent methods of different classes.

Comments!

- Legal stuff

- Explaining intent

- Warning consequences

- Todo!

Test Code

- 1 assertion per test

- Clean tests follow FIRST

- Fast

- Independent

- Repeatable

- Self-validating

- Timely

- Im not tryna remember this

Refactoring

- MY BELOVED!

- Doesn’t change behavior, but makes it beautiful.

RQ_SET2

I have about an hour and a half. Plenty of time!

So we use when

Model does server-sided stuff and returns things the viewer might want (of course passed via the presenter)

@RunWith(MockitoJUnitRunner.class)

public cclass ExampleTest {

@Mock

MainActivity view;

@Mock

Model model;

@Test

public void testPresenter() {

// When() substitues func result to certain thing

// if you don't specify the thenReturn, it will return false, 0, null, etc.

when(view.getUsername()).thenReturn("abc");

when(model.isFound("abc")).thenReturn(true);

Presenter presenter = new Presenter(model, view);

presenter.checkUsername();

verify(view).displlayMessage("User found"); // The view returns this cuz presenter did check and find user.

// If you don't set when, then u will get default values.

// assertEquals(view.getUsername(), null);

// Getting the value of some arg during the test.

// wanna know "what value of the arg was passed"

ArgumentCaptor<String> captor = ArgumentCaptor.forClass(String.class);

assertEquals(captor.getValue(), "user found");

}

}