Running code

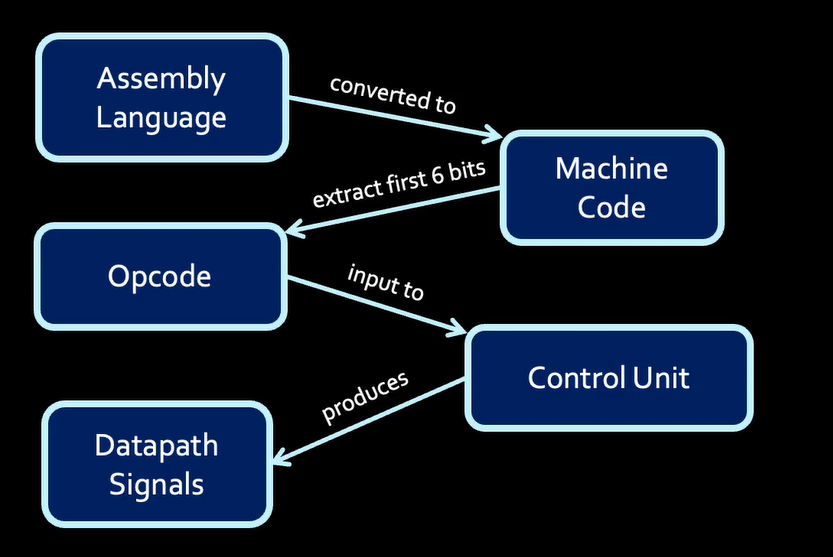

- Code turns into machine code instructions (1’s and 0’s as “words”)

- Those are saved as an executable

- Processor loads in executable’s instructions. Then the processor does the instructions.

Program = sequence of instructions in machine code

- Like from last week, the

opcodeis what determines the type of operation. The rest specifies the instruction more after that. - To make machine code readable, each line can be presented as a mapping via assembly code

- Assembly is something we can organize / understand. The machine code is what the processor can actually run.

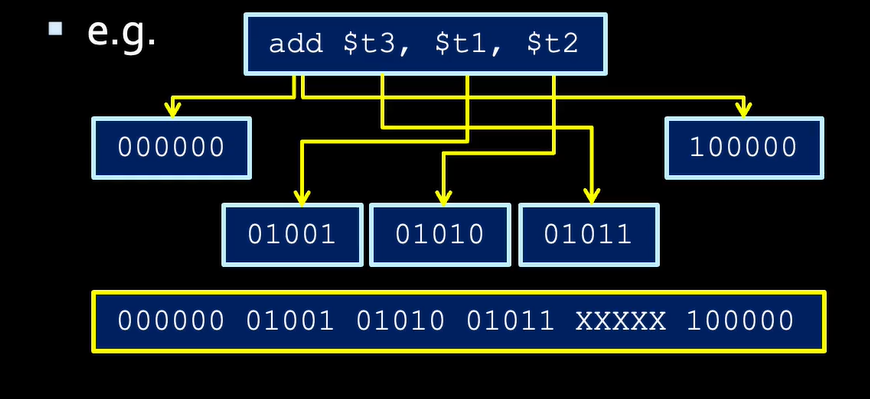

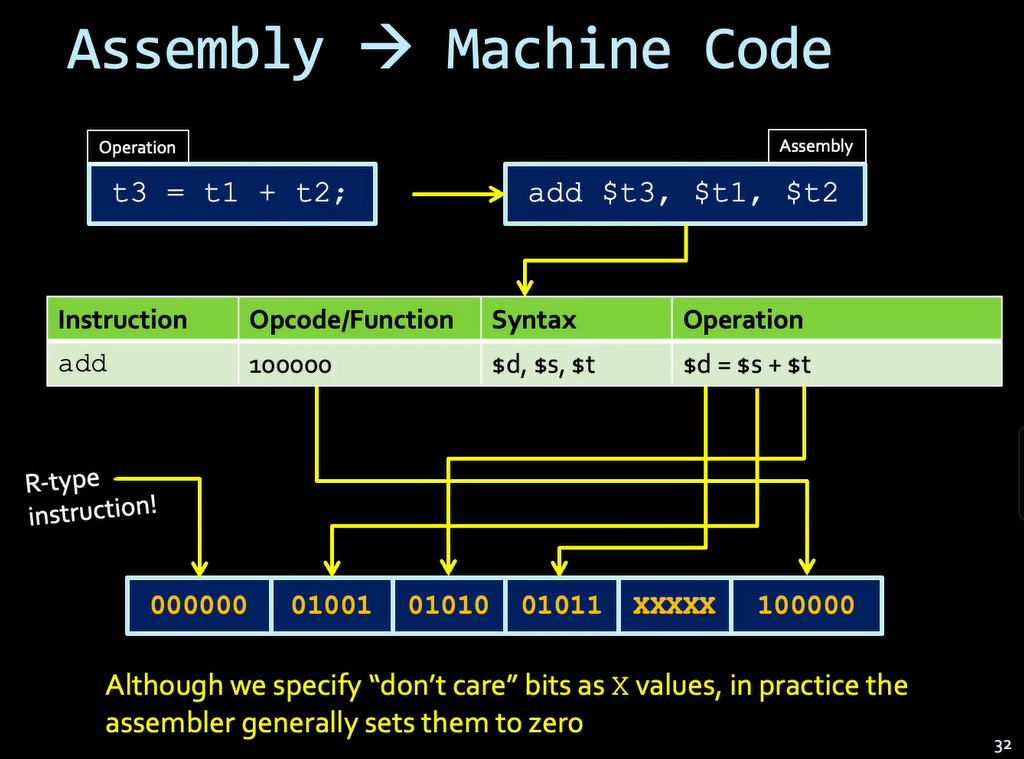

C = A + Bwhere A is at$t1, B is at$t2and C goes to$t3The assembly instruction is

add $t3, $t1 $t2Then that’s translated to machine code:000000 01001 01010 01011 00000 1000001:1 mapping!

Assembly is super low level. No variables. No loops. No nothing.

- There are many assembly languages for different architectures!

Why learn assembly? It helps you really get computers and programming!

Assembly to Machine Code

- Encoding is the reverse of decoding

- To encode

add $t3, $t1, $t2, we first figure out the opcode. It’s ar-type! - If you have the table, you’d know that it’s

000000 - For adding, that’s

func = 100000 $t1is the register010001(9)- You can figure out the other 2 as well

- And boom!

- To encode

- The “shift” bits are

XXXXX(don’t care) but in reality just put00000cuz why not

A program that turns assembly into machine code is not a “compiler”. It’s an “assembler”

- No fancy compilations happening

- Writing an assembler is super easy so long as you have the table

- The assembly instructions turn into code, where the 6 bits are your opcode. This goes into the control unit which fires the necessary datapath signals to make the instruction happen

MIPS is an architecture! It has an assembly language!

- ”Microprocessor without Interlocked Pipeline Stages”

- It’s a RISC architecture (we give a relatively small but fast set of instructions; complex instructions are built out of simple ones by the compiler and assembler)todo

- It is a register-to-register architecture

- ”load-store”

- If you want to operate on some memory, you have to load it into a register first, and store the result back into memory.

- So every source data comes from registers (unlike other architectures where it comes from the memory directly)

- This falls in line with RISC. instead of operating directly on memory, it’s split into:

- Load operation

- Computation

- Store

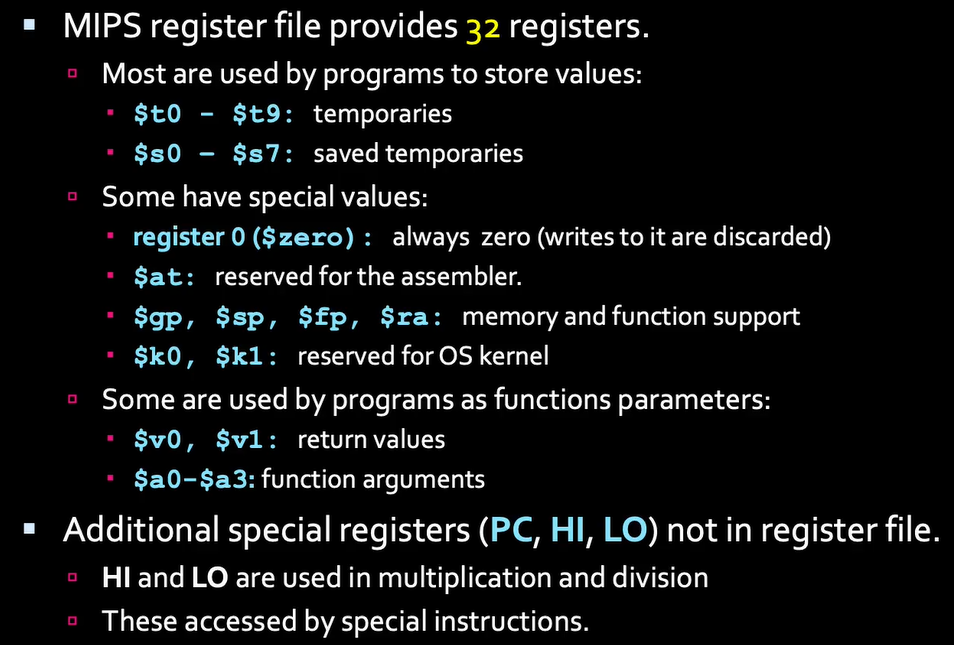

- MIPS register files have 32 registers. Numbers are kinda wack so we use short names like v1. There is also 0, $1, etc. if you wanna

- These registers have a certain format!

- Recall PC is the register that stores which operation we are currently running

Then he goes over a bunch of assembly instructionstodo there is a table

- There are 8 types of assembly instructions, but only 3 types of MIPS instructions!!!?!

- That’s the diff between the microarchitecture and the instruction set architecture (ISA)

- The ISA is the set of instructions the processor can do

- This affects access to registers, address and data formations, execution model (?), etc.todo what…

- So the ISA is the design with the ideas on what has to be there. The microarchitecture is the implementation of the design. Common ISA should mean same instruction set.

- A “kind of contract” between the processor and programmer

- If the programmer sticks to the ISA, the processor guarantees the instructions will work correctly

- The Microarchitecture is the implementation of the ISA on the processor

- This affects things like cache, pipelines, branch prediction, datapaths, etc.

- The same ISA can have many microarchitectures that implement it

- The x86 ISA, over the last 35 years, have had many implementations!

- E.g. intel, who made the x86 ISA, has created many many microarchitectures that implement this ISA

- Computer Architecture is the combination of both of these

RISC-V

- FOSS ISA

- Anyone can implement it!

- Code that compiles to RISC-V should be able to work on any other RISC-V processor

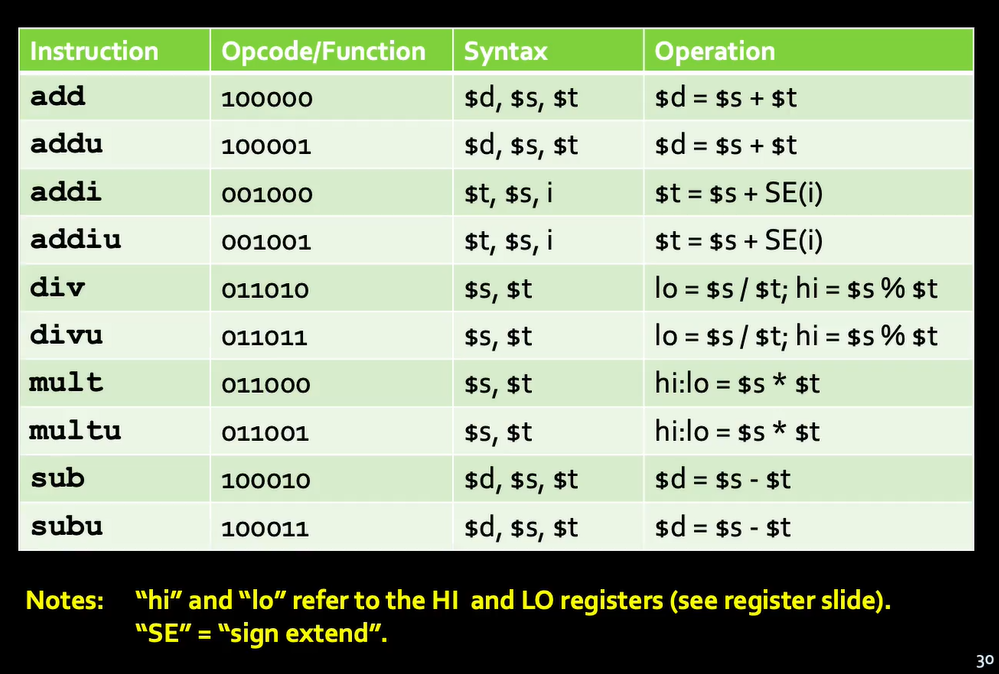

ALU Instructions

- Add and Addu add S to T and store it in D

- Addi (add immediate) does a sign extension to the

iimmediate number- Remember sign extension is going from

1001to11111001for instance.todo where in the notes was this!? Idk but at least I remember it now

- Remember sign extension is going from

- addiu (add immediate unsigned) to be explained later

- div and div unsigned divide s with t. The result of dividing goes to

loand the remainder goes tohi - mult multiplies s by t and outputs the first 32 bits to

loand the last 32 bits tohi! Wow thats cool - sub and subu are self-explanitory

SE(i)means sign extension for the immediatei

All but addi and addiu are R-Type instructions. addi and addiu are I-type

- The instructions with an immediate are I-Type (these use an immediate/constant not drawn from a register, whereas R-Type’s have all their operands drawn from registers)

- In all of these, the “register we’re going to” is the last of the register-related params. So

$dis the 3rd register. The first two are for$sand$t. But in assembly it’s nice enough to keep it in a logical order so thatd = s + t. otherwise the instruction in machine code is in order ofs, t, dwhich is not intuitive…

Unsigned Instructions

- The only difference between

addandadduis thataddudoes not throw an trap / exception if there is an overflow.adddoes. - For

multandmultu, neither check for overflow. What’s the difference then?- In

multu, the upper bit is now an actual number which you multiply. - So

1010*1000results in01010000(80) if the numbers are unsigned - But

1010*1000results in00110000(47) if the numbers are signed

- In

- For this course, we assume overflow never happens

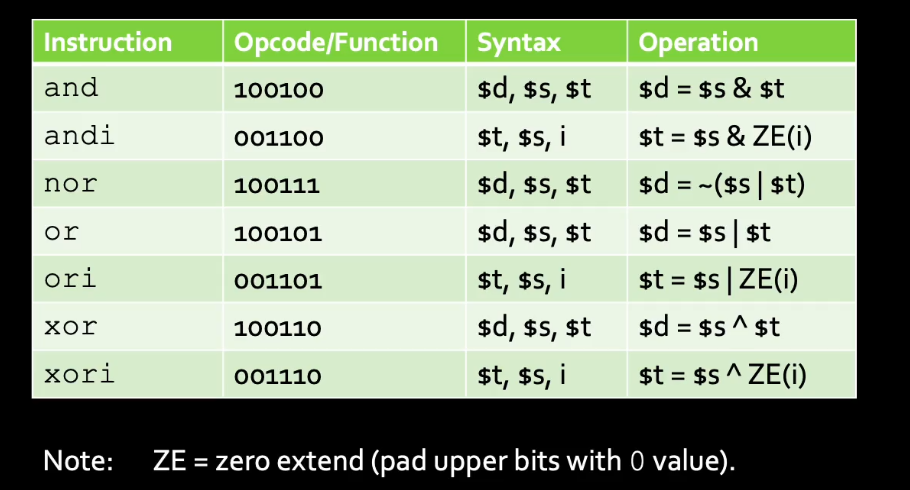

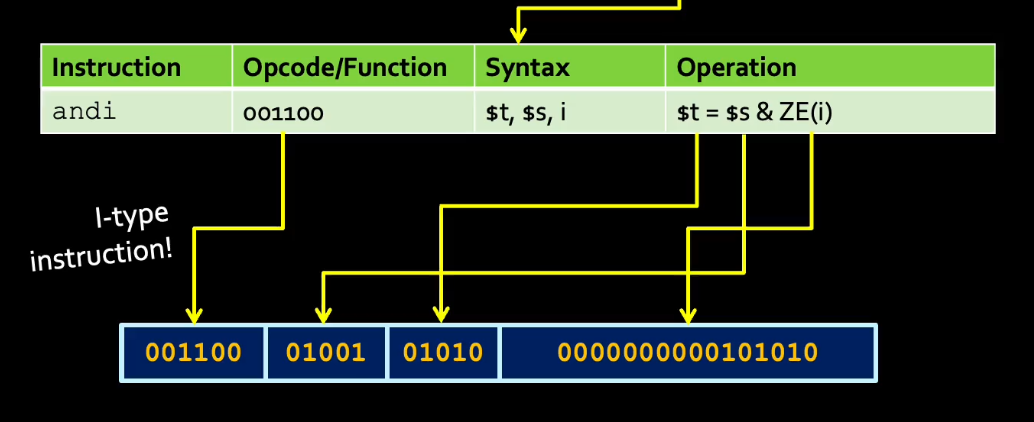

Logical Instructions

- andi, ori, and xori are the immediate versions

ZE(i)is zero extension (instead of sign extension) (padding upper bits with0values)t2 = t1 & 42is equivalent toandi $t2, $t1, 42iis42(constant! immediate!)

- Idk why the immediate is so long lol. Oh no i get it now, it’s cuz it’s a constant of size 32-bits at most. In fact the immediate here is too small! We’d have to zero/sign extend it

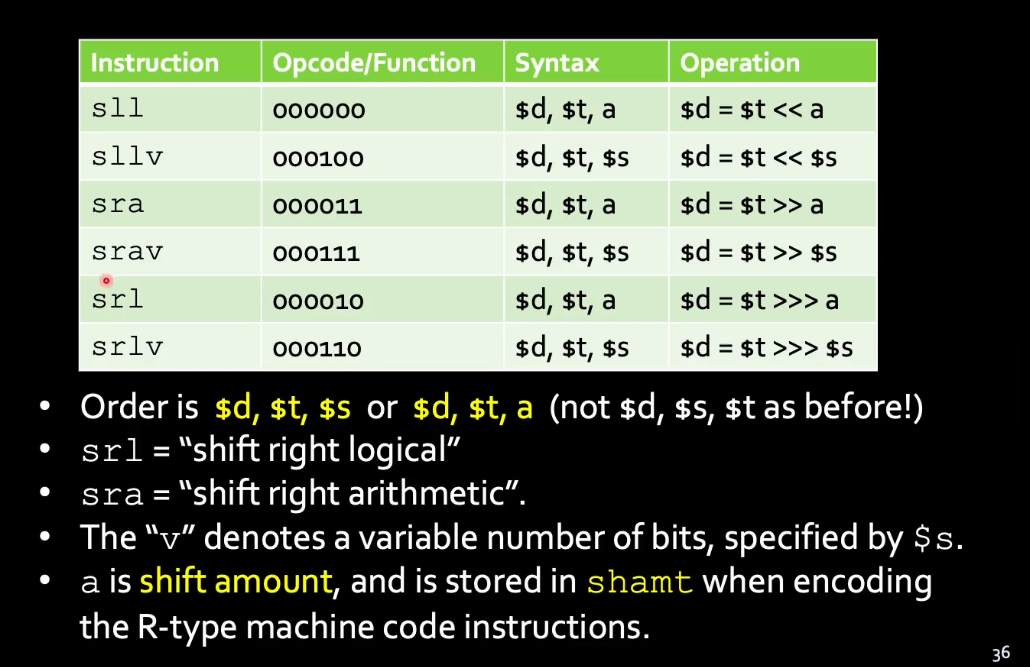

Shift instructions

- Shift left logical

- Shift leg arithmetic

vversion- Instead of taking the number of bits to shift from a constant, it’s taken from another register. So… like inverted lol

vdenotes a variable number of bits specified by$sais the shift amount- The v instructions instead of taking the # of bits to shift from a consatnd, it takes it from a register.

- ”non-v” the shift amount is stored in the shift amount field of the r-type instructiontodo at 34:40 i think he misspoke cuz this cannot be r-type

- Instead of taking the number of bits to shift from a constant, it’s taken from another register. So… like inverted lol

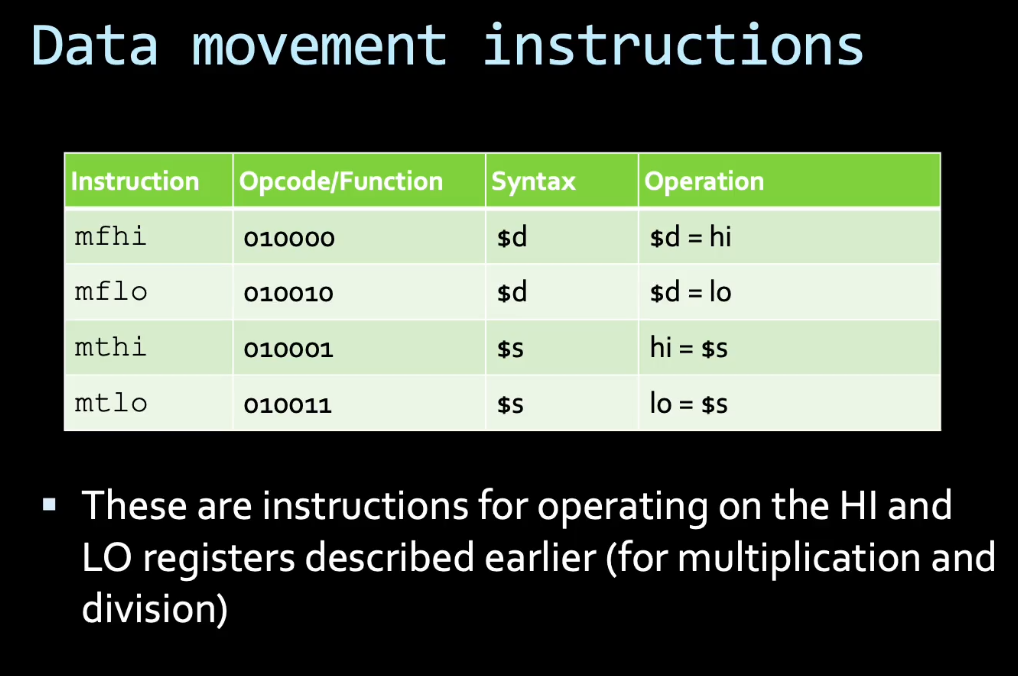

Data Movement Instructions (for HI and LO)

mfhi= “move from hi” returns thehiand stores it into$d- Same with

mflobut for “move from low” mthi“move to hi” moves $s into hi- same with

mtlobut it’s “move to low”

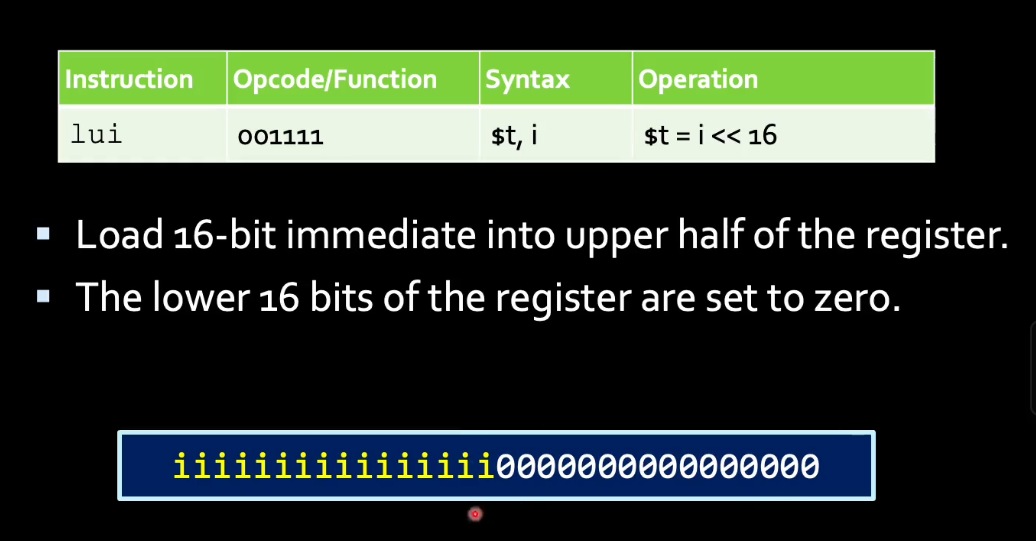

lui ⇒ load upper immediate

- Remember immediate fields are only

16bits. Registers have32. - lui loads the 16 bits into the upper half of the 32 bits. it shifts the immediate 16 bits. the lower 16 bits are set to 0.

Not all R-Type instructions have an I-type

- we have addi but not subi

- we have ori but not nori

- we have div but not divi

- This is b/c of the RISC principle: If an operation can be done through existing operations, it shouldn’t exist (redundant)

addi $t0, -1is equal tosubi $t0, 1pretendingsubiactually exists

Pseudoinstructions

- They look like assembly instructions but they are actually turned into one or more assembly instructions

- E.g.

move $t5, $t4copies$t4into$t5.- This translates to

add $t5, $t4, $zero. Wow

- This translates to

mul $s1, $t4, $t5(multiply and store into$s3is the same asmult $t4, $t5mflo $s1

li(load 32-bit immediate) is also super important. It loads an immediate into a registerli $s0, 0x1234ABCDis equivalent tolui $s0, $s0, 0x1234ori $s0, $s0, 0xABCD

todo there is also la but idrk what that does. it stores a address of a label into a register…?

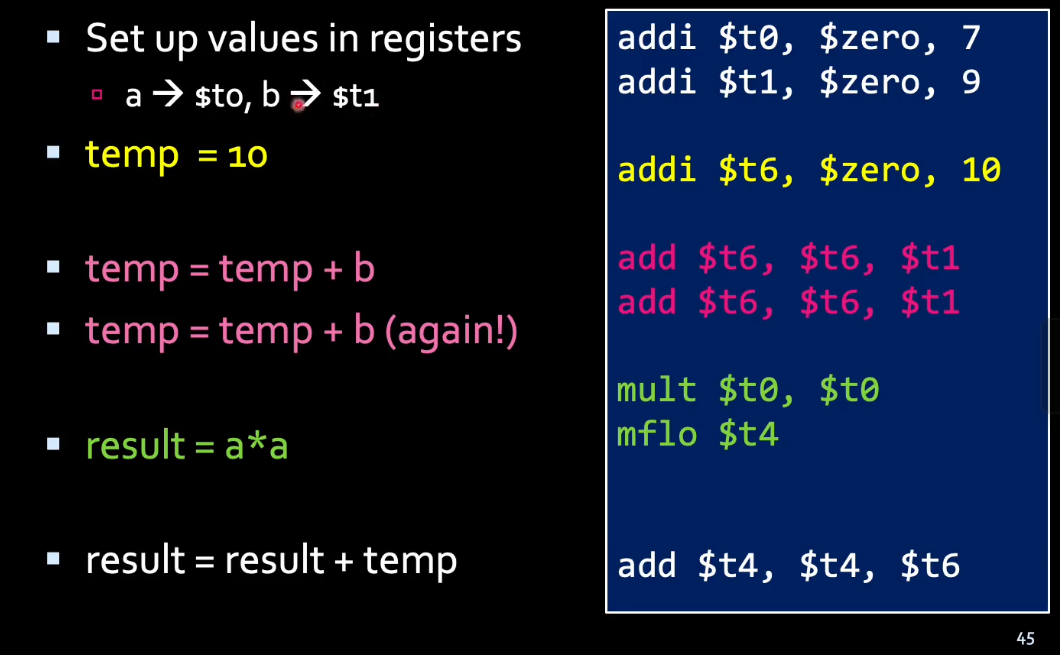

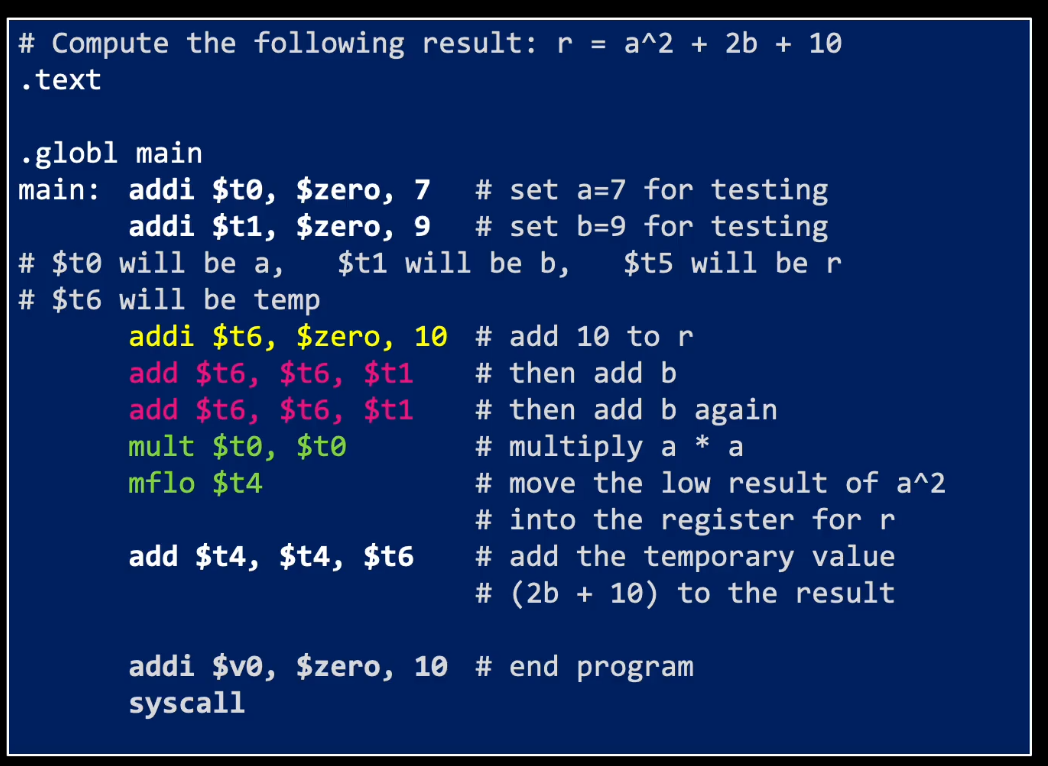

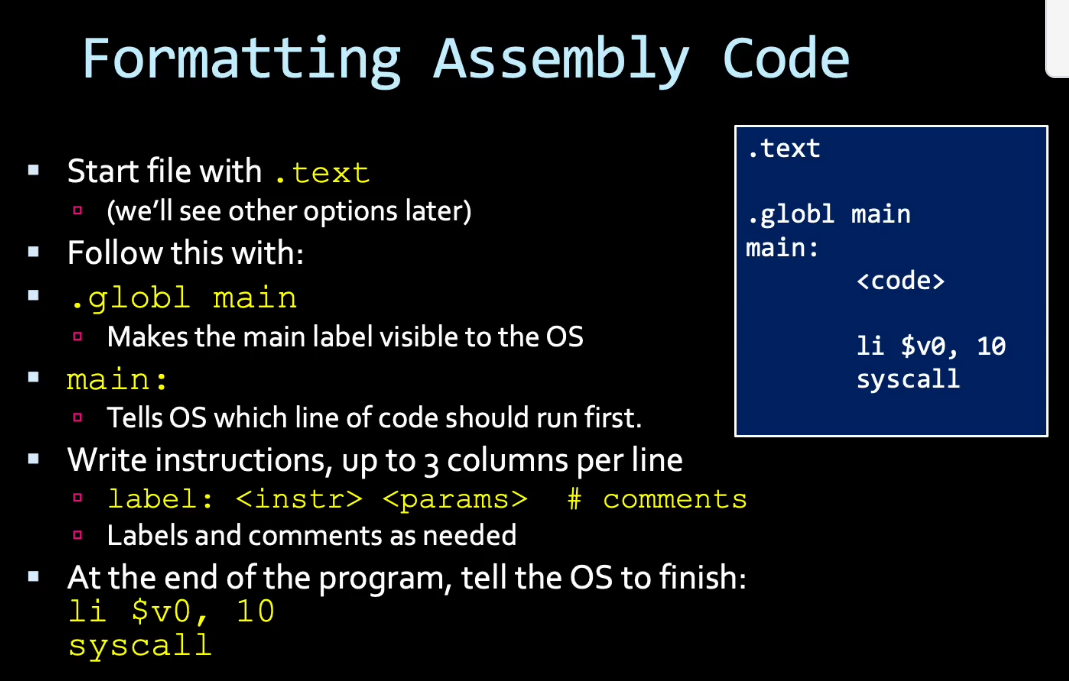

Making a program

- We set aside registers to store data

- There are sections of instructions to manipulate this data

straighforward

straighforward

- the last 2 lines we go over next weeks

- 3 columns are the labels, the instructions, and the comments

Finding

a^2 + 2b + 10