For addiu there is a type. we do zero extension, not sign extension (sign why? the number is unsigned!)

Bitwise logical operations

- For each 32 bits of

$sand$twe AND them.

sll ⇒ shift left logical (for an immediate)

sllv ⇒ shift left logical (for a variable v)

sra ⇒ shift right arithmetic

#todo it’s in the slides oops

- ”immediate values are encoded in the instruction set”

For non-linear code break things up to make it less complicated / high level

To “goto” another bit of code, we jump or branch

- Branching happens based on some condition (like an if statement!)

beq⇒ Branch if equalbgtz⇒ Branch if greater than zeroblez⇒ Branch if less than or equal to zerobne⇒ Branch if not equal These all take two things to compare, and alabelwhich updatespc(the instruction we are executing)

Comments are really important.

Labels look like main: or end: and the like. Labels are word that describe the location of the first instruction of a new “block”todo How do we know where they end though? (Okay we don’t lol. It will keep going and execute the code in the future labels :p It’s really not smart at all! Use j END or something like that as the last line of a branch to make sure it doesn’t continue running the wrong code 👍)

- When we “branch”, we say a “branch has been taken”

- Otherwise we say the “branch was not taken”.

PC += 4like normal Branching is limited! Cuz you have those two compare registers as well as an immediate for the label value - Remember that immediate is the offset from where we are and where we want to go.

- This is good but it still is a constraint with how far we can go (we only have

16bits of “distance” we can use in total)jfor jump goes to another label without any condition

- This is good but it still is a constraint with how far we can go (we only have

There are algorithms for branching && and ||

- todo You can go through the slides but they are very intuitive!

Jumping

j = jump always

jal = jump and link

- It jumps, but before that u store the current location and store in RA

jalrjump and link from registerjalrandjrare R-Type cuz they involve reading from a register. - Can you branch from registers too or nah!? (Ans: Yes with pseudo-instructions)

Comparison instructions

slt compares s and t and sets d if it is less than it (writes just 1 if true) otherwise it stores 0

- Basically it stores a boolean!

Then the other 3 are obvious derivatives:

sltu,slti, andsltiu

And from those you have a bazillion pseudo-instructions for branching using the above.

Loops!

- For loops there are no new thingys. The gimmic is using labels for the things done each loop (

UPDATE) and the things to keep the loop going (START) - While loops are simpler in that they don’t need the

STARTbranch if i understand correctly.

OS Services

- System calls are what the processor does to communicate with the operating system

- For Input, output, files, getting time, and ending program. Y’know, kernel things!

v0is the number of the servicea0-a3are for the args of the service- Then you just call

syscallto run the service of typev0 - The results go to

a0(waittodo is that a typo? That isn’t a return type at all!)

Memory operations

Always either load or store. Storing = storing into registers (because of the load-store design)

These operations have 3 parts for the name:

lfor load andsfor storebfor byte,hfor half-world, andwfor wordufor unsigned (or blank for signed) (changes if we zero extend or sign extend)- in

i($s),$sis a value from a register.iis an immediate $tis the destination register. It’s the data we are either reading or storing depending on the operation- todo i am not getting this very well

Yeah i am quite lost

Example time

lh $t0, 12($s0)

- Address is

s0+12. It’s signed so we sign extends0 + 12and that goes intot0 sbtakes the lowest byte intot0. The address starts froms0 + 12- The offset thing is useful for dealing with structs / stacks / arrays!

- So that offset can be for, say, indexing!

”A view of memory”

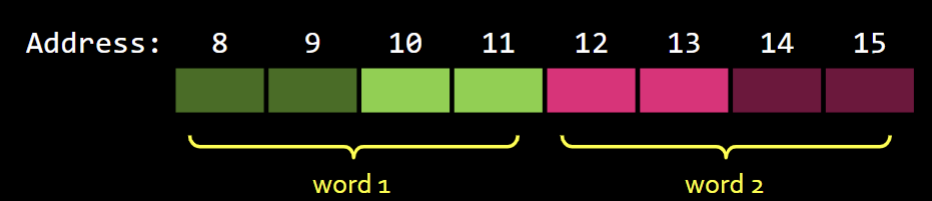

- Words must be on addresses divisible by 4. It must be “aligned”!

- Misaligned memory access results in errors (exceptions)

- Words are word-aligned (divisible by 4)`

- Half-words are divisible by 2 (even addresses)

- MIPS

- Word lines have 32 bits which 4 different addresses. When reading or writing, we read all 32 bits at once usually.

- If we want to load a word starting at position 10, then we would need 16 bits from one word, and 16 other bits from another word. That would be wack!

- Some assemblers might know what’s up and only read the correct halves of the words, but truth is it’s not always like that

Variables

- We have a label for the variable name (i.e.

var1:is a label, also a variable name) - Depending on the size, you use

.word,.byte,.half, and.space. These are assembly derivatives .spaceallocates 40 consecutive bytes but they are empty- That all goes into

.data(vs..text) .dataindicates the start of the “data” section where we got our variables.textis for your instructions

la , move, and li

la⇒ Load address of alabelinto$tmovemoves thingy from$sto$tlimoves a 32-bit immediate into$t- It does this by loading the top and bottom halves separately (remember i-type instructions cannot support 32-bit inputs.)

todo GO to the A*B+C example… why can be only move from lo? Will the result retain it’s value… OH WAIT IT DOES

Endianess (WHAT KINDA WORD IS THIS)

Two words in hex = 1 byte.

Endianness determines the order of the bytes (different processors word differently)

Big Endian (big end first)

- The most significant byte is first. in

0x1234ABCD,12has the biggest value.CDis the lowestLittle Endian(little end first) - Opposite. It’s obvious!

CDwould have the biggest value instead.

This is mentioned in lecture because they cause headaches

I caNNOT STOP LAUGHING