Utility programs

Considering this took 6 slides, I’m p sure it’s important

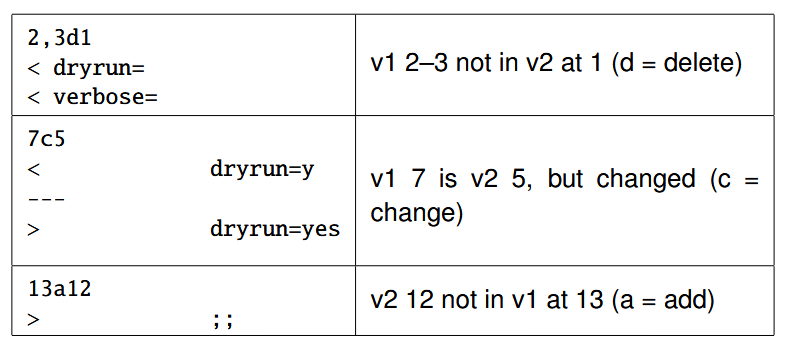

diff takes two files, shows the difference in terms of lines to add, delete, and replace.

Exits 0 if no diff, and 1 if diff.

- 2, 3d1 = Must delete lines 2, 3 at position 1 in V1 to get to V2

- 7c5 means you must change line 7 of V1 to get to V2

- 13a12 means you must add line 13 in V1 to get to V2

The

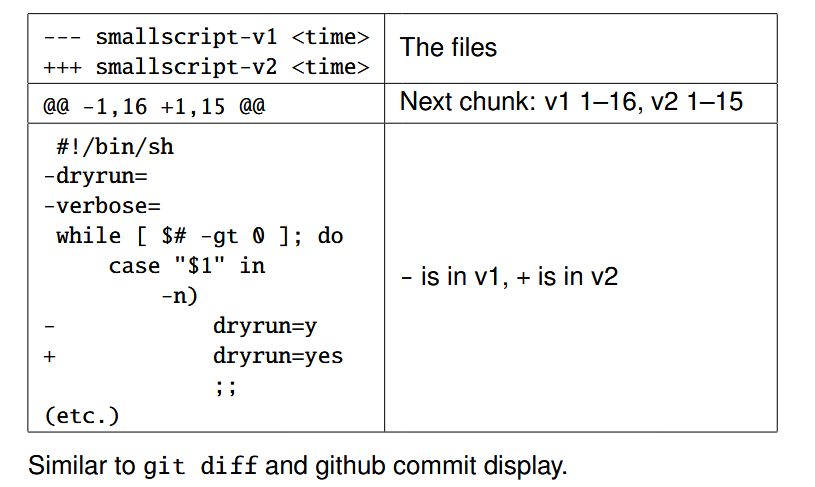

-u“Unified” output

Grep

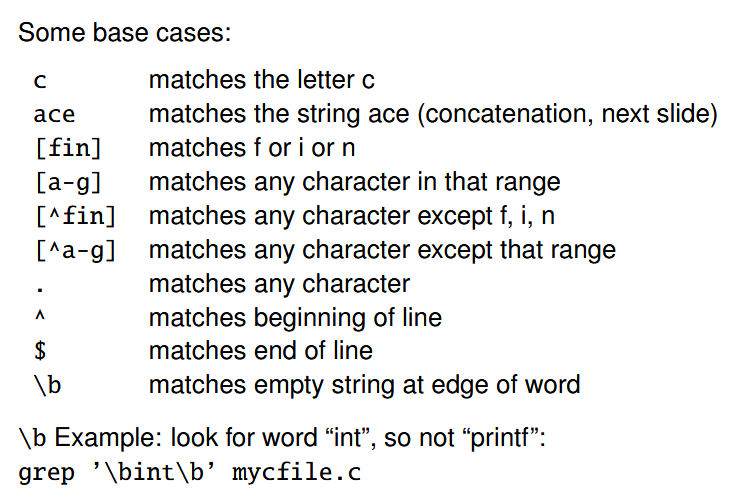

Searches in a text file via regex.

Outputs matching lines

It returns 0 if found and 1 if no match.

For instance, to pick out an HTML start tag, you can do grep '<[a-zA-Z]*>' index.html

More weird grep stuff with -E idk

Sort

Takes a file, sorts it.

-b ignores leading blanks. -k defines the “key” to sort. You can use this arg several times over.

For instance, sort -b -k 2,2 -k 3,3n will sort based on the second column (via comparing strings). If two strings are identical, it will fall back to

find looks for files naming a certain pattern. Does it recursively!

Takes a bunch of directories and recursively goes through them. Then it finds the files.

To match name, you do -name '*.pdf. To specify type (file or directory), you do -type f or -type d, etc.

Lastly, for a certain period of time, you do -mtime +3 -mtime -6 for 3 to 6 days ago.

You can also use… logical connectives… aaaaaa

find mydir ’!’ ’(’ -mmin +3 -mmin -6 ’)’By default the action is -print but you can also do -delete

find . -name ’*.py’ -print -delete

- Albert is #1 python hater

Data Types slides

Let’s see if I can get these IO, and the modularization slides down before I sleep (20 mins each… that’s doable right?) You know memory already. Adding pointers really adds by the size of the data

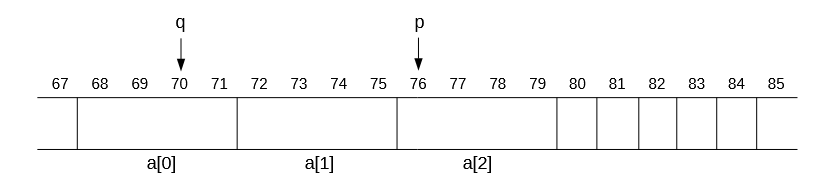

int a[3]; // assume this is stored at position "68"

int *p = a + 2; // 68 + 2* sizeof(int)

There are a bunch of common areas in memory:

- Text (for actual code. Functions point to these)

- Global stores global values

- Stacks are for function calls. You know them

- Heaps are for memory allocation / deallocation.

Global Variables

- Type: Top-level, function private

- Top level = outside of functions

- Function private = only in context of functions

static int function_hobo = 10;

- Subtype: whole program, module only

- Module only =

static int module_var = 50;- No other program can read this!

- Whole program =

int global_var = 50

- Module only =

Literal integer notation

- 3 for an INT

- ’c’ for… also an int (but it’s a char)

- 3U for an unsigned int

- 3L for a long

- 3UL for an unsigned long

- 3LL for a long long

- you get the idea.

To print a long unsigned, you use

%lu

Number type conversion

- When big goes into small, you should be explicit. So, if a char goes into an int, you’re sure to be safe. If an int goes into a char… well if it fits, it will make sense. Otherwise, integer overflow my beloved

Implicit Number Promotion

Int ⇒ Double type deal. The rules be complex, but usually smaller range gets turned into bigger range. integer divide by int means int gets turned into double first.

Enums

enum rps { ROCK, PAPER, SCISSORS };

enum coin { HEAD, TAIL }- It defines integer constants. You can have enum variables via

enum rps a;orenum coin cand set them viaa = SCISSORS

Onions 🧅

They taste the best when cooked. On pizza they are amazing. Burgers too. God I love onions.

Unions

union my_union {

unsigned short s;

unsigned int i;

unsigned char b[4];

};

Assumes the size of the largest field. They all share this tiny bit of memory. It’s up to you to know which one is being used! The memory starts from the address of the union upwards (i.e if the address is 128, all the fields have the same address)

- You can access all fields via

a_union.s,a_union.i, anda_union.bat the same time. It’s all your choice which to use.

The Tagged Union Idiom!

Okay you can do:

union my_union {

unsigned short s;

unsigned int i;

unsigned char b[4];

};…and reuse this union - we’re essentially “defining” it here - OR you can do

union {

unsigned short s;

unsigned int i;

unsigned char b[4];

} a_var;…which defines a variable with a certain union type. OR you can do both at the same time, but let’s ignore that. For the tagged union idiom, it’s best to have the variable be of it’s own union type.

struct taggedUnion {

enum { INT, DOUBLE } tag;

union {

int i;

double d;

} data;

};

struct taggedUnion itemName;

typedef struct taggedUnion typeName;

struct int_or_double a[10]; // an array of size 10 for these int, double hybrid thingystypedef

Remember the second way you can define a union, and how there’s a variable name at the end? Well now look at that first way. The idea is, add typedef before the keyword (struct, enum, etc.)) and at the end, where the variable name would be, write the name of this new data type!

Examples:

double; // This is of type double. No name, so its totally useless. But its valid code lol

typedef double some_var; // This is defining a type named some_var, which is identical to a double.

enum coin { HEAD, TAIL }; // Defines the type of a coin

typedef enum coin { HEAD, TAIL } coin; // aliases the thing to "coin". Yay, so easy. N name clashing problem either (you either use "enum coin" or just "coin"; they different, but don't clash!)He mentions this is legal as well:

typedef struct node {

int i;

struct node *next;

} coin;

typedef enum coin { HEAD , TAIL } node;enum coin= the actual enum typenode=enum coincoin = struct nodestruct node= the actual struct for the node- So it’s legal, but very confusing and ugly and bad

Function pointers!

int (*a_func)(); // Param names / types are optional but ignored. It returns an int, takes nothing.

(*a_void_func)(int some_num); // This function returns nothing, takes in an integer though.You can use typedef with these to make them spicy

typedef char (*F_out)(int). The name of the type is F_out and it’s for all function pointers of the type. Easy breezy.

Pretend we have a function that takes a function and returns a function

typedef char (*F_out)();

typedef int (*F_in)(char, char);

F_out (*thing)(F_in f);You DON’T need to specify that

fis a pointer, sinceF_inis already a function pointer type. The pointer-y-ness is included.

I/O

Probably the last thing I do before I go to sleep

For regular files, you can seek to positions. Cool. File functions work with FILE * all the time! It represents a “stream state” since all file contents are accessed as “streams”

- In reality, “FILE” should be “stream” and we should be doing “stream” functions. This makes sense. Files are file descriptors. Those are different!

fopen opens a file of a certain name (you pass a string and mode)

The modes can be r, w, a (a for append). The + does “the other thing”

Note, any mention of

rmeans when reading, if the file exists, it does nothing, but if the file doesn’t exist, it will throw an error. Likewise, for any mention ofw, if the file exists, we truncate it. If it doesn’t exist, it’s created. Fora, it doesn’t truncate (keeps it as is) and if it doesn’t exist, it’ll create it.

- So r+ means it can read and write (does reading-related things when opening)

w+means it can write and read. It’ll do the write-related things (so it’ll create it no exist, truncate if does) and then allow for reading. returnsNULLif error (no file is returned)

For window something something

bfor binary files

Close

int fclose(FILE *stream) closes a file stream!

fprintf prints into a file stream a string of a certain format, and then u throw in a bunch of args!

fscanf takes a file, reads the string, and then outputs the data into the succeeding variables of the format.

stdout, stdin, etc. are pre-opened. Remember, they are of type FILE* (not just integers! That’s for STDIN_FILENO, etc.)

putchar (stdout), and putc ()

- Returns the character written if success, and EOF if error

getchar and getc

Returns the character read if success, or EOF if error / end of stream. EOF is not a character in the file; it’s just a special return value.

Since EOF fits into int, the correct way to call getchar and getc is by returning the output into an int first, and then down casting it into a char

String I/O time

int fputs

Writes a string verbatim into a stream. Returns EOF if error. puts also adds a newline.

`char *fgets

Reads n-1 characters or until (and including) newline. The nth character is reserved for the null terminator. n is the size of your dest/“string buffer” array

Returns NULL if no string

Arbitrary I/O (reading x amount of data of different types)

size_t fread(void *dest , size_t s, size_t n,

FILE *stream)size_t fwrite(const void *data , size_t s, size_t n,

FILE *stream)void *destis a pointer to the data of your choice- e.g. if you are writing to an array of size 10, then the pointer is the array, the

sissizeof(arrayItem)and thenis 10 (10 items in the array) - Returns how much items it read.

- e.g. if you are writing to an array of size 10, then the pointer is the array, the

fwriteis the same. It takes a reference to an array, the size n stuff. Outputs to array.- Return show much it wrote

Seeking

int fseek(FILE *stream, long i, int origin)

int origin = SEEK_SET, SEEK_END, or SEEK_CUR (current pos)

Returns -1 on error, 0 for success.

long ftell(FILE *stream) returns current position of stream.

feof and ferror

Getters for the fault and end fields of FILE stream.

When a read doesn’t read any more (i.e. it hits the end), end is set to true. Therefore, calling feof will return 1 since we hit the end! 0 for not the end.

Same for ferror. if a write is unsuccessful, ferror will be a non-zero number.

This is what i forgot during the test.

errno

It’s a global variable. Easy as flip to be overridden

There are a bunch of different values

You print it via void perror(const char *prefix)

char *strerrno(int errnum) and char *strerror_r(int errnunm, char *buf, size_t buflen) return the message of the errno

Buffering

- For writing, data is accumulated before the whole chunk is written (not done one at a time. That is wasteful)

- For reading, it asks for a large chunk info buffer, then gives you small bits from it (e.g. like via

getcyou only get 1 char from that buffer)

int fflush(FILE *stream)writes to buffer immediately Returns 0 if success, and EOF if error.

To change buffering, we do int setvbuf(FILE *stream, char *buf, int mode, size_t n)

the int mode can be 1 of 3:

_IOFBFis for full buffering (so like, when you write, it will keep writing until we close)_IOLBFis for line buffering. When a newline is hit, we flush_IONBFis for no buffering. Changes are immediately flushedbufis for buffer space. IfNULL,setvbufallocates its own (?)

todo Probably important to remember stdout is line buffered in terminal, and full buffered in file/pipe.

- Same with stderr, stdin, but with different rules

Modularization

C code turns into a .o file (this is machine code. It first does preprocessing, and then turns that preprocessed code into machine code). The .o files, alongside libraries, are linked into the final executable.

Pre-processor directives

Macros

#define is a macro. It literally substitutes text.

Also #undef undefines a macro

#include

- Shoves the whole content of the file where it is. So including a

.cwill shove the whole.c. But it’s better to do.h’s instead of course. - If you want gcc to search for more dirs, you use the

-Iflag many times for all dirs you wanna search

Conditional Compilation

#ifdef MY_FLAG

fprintf(stderr, "Hey, this runs if the flag is defined!");

#endifYou can enable a flag when compiling with -D MY_FLAG

Modularity time

Implementation is in 1 file, header in another. Files that implement the header will use the 1 implementation given

Declaration = name and type

- function prototype is function declaration Definition = implementation

Header files have

- Macros

- Type definitions

- Function prototypes

- Global variable declarations Usually struct definitions are in the header files. You can technically have a struct declaration without definition. It acts as an “abstract” type (no known fields, or size — unless we’re talking about the pointer of course! That’s always 8 bytes)

typedef struct node nodetype;

// Now "nodetype*" available .

struct node {

int i;

nodetype *next;

};Global Variables

extern int myvar; can be in header. Doesn’t actually define it. Just states “existence”. Only 1 .c can request to “define” it properly (allocate an address, etc.)

doing int myvar; is only possible in 1 .c! But extern int myvar; can be in many!

Double #include chicanery

- If you define twice, you will be yelled at.

#define _FOO_H ⇒ Means _FOO_H has been defined. If not, we define everything

#ifndef _FOO_H

#define _FOO_H

typedef struct node {

int i;

struct node *next;

} node;

#endifMakefiles are used to compile when changes are made and not “every time”

bb.o : bb.c bb.h rect.h

gcc -c bb.cbb.ois the “target”- If any of the files are newer than

bb.o, then we run the recipe

- If any of the files are newer than

- The indented thing is the recipe

- The things after the

:are prerequisites Runningmake targetrun a run matching the target. It’s normal to have analltarget so you can domake all - This simply triggers using other rules to build all the executables you have

all : myexe1 myexe2 myexe3

.PHONY: all.PHONY means “all” is not a file to be made. It’s just a label to be called upon by make

You can also have a clean label that always just removes all files.

clean :

rm -f *.o myexe1 myexe2 myexe3

.PHONY: cleanVariables

CFLAGS = -g means the variable $(CFLAGS) is -g, just like shell script

You can also set variables when calling make via make CFLAGS='-g'

Env vars become vars. Also vars become env vars for running recipes

mainprog : mainprog.o bb.o rect.o

gcc -g $^ -o $@

##### $^ = all prereqs | $@ = target | $< = first prereq

%.o : %.c

gcc -g -c $<

clean :

rm -f *.o mainprog .depend

.PHONY: clean

.depend: mainprog.c bb.c rect.c

gcc -MM $^ > .depend

include .depend- .depend is run, which creates a file with a bunch of dependencies. They look like

mainprog .o : bb.h rect.h

bb.o : bb.h rect.h

rect.o : rect.h

Which is the tedious thing we wanted to avoid doing! Wow! Isn’t that convenient Otherwise

%.o : %.c

gcc -g -c $<

mainprog.o : bb.h rect.h

bb.o : bb.h rect.h

rect.o : rect.hsimply means any .o can be built from a .c

The Unix File System (nightmare nightmare nightmare nightmare nightmare nightmare nightmare)

- Each file has an owning user and owning group.

- Access perms are for read, write, execute perms

- For regular files, it treats as program/script to run

- For dirs, it’s special:

- For read, you can see filenames

- For write, you can add/delete files

- For execute, you can CD into it and pathfind through it.

rwx--x--x- Means the owning user/group can discover files in a directory unless you explicitly give the directory to someone (then they’ll be able to cd into it just fine!)

Changing perms

chmod ⇒ Change mode (terrible as frick name)

- Changes permissions of file.

chmod u=rwx ./my_file.txtmeans the user can read, write, and execute the file given- You can change the owning user / group with

chownandchgrp- But

chowncan change both the user and the group (group is after:, user is before it)

- But

i-node

- The file system has a table (array) of i-nodes

- i-node number = array index

- Each file and directory is identified by its

i-node(NOT filename!) - It stores a files directory and metadata

- But it does NOT store the filename. Filenames are in directories.

- Directories are mappings from filename to

i-nodenumbers - The structure of directories depends on system, but

‘opendir’, ‘readdir’, ‘closedir’open directories portably (OS-agnostic) - Two filenames with same i-node means two

direntries to the exact same file!

Hard links

- A filename that has the exact same i-node as another file

lncreates this for regular files. You can’t hard-link directories. Only.and...

Unlinking

- There is no “deleting” of a file, only unlinking. When you unlink a file, you’re really decreasing the reference count of the file. If positive, there are still refs, so we don’t free it. If zero, then we free it.

- That’s why the syscall for “deleting” is

unlink.rmis just a wrapper forunlink

Soft links / symlinks

Forwards you to another pathname. Most syscalls do symlink forwarding. I.e. a symlink to a symlink to a symlink are all followed till we get to a final OG file. If the symlink goes to a ./ relative file, then it’s relative to where the symlink lives. You can symlink to a directory!

ln -s path linkname to create a soft link.

Hard link ⇒ accessible Soft link ⇒ symlink is denied (has to follow path, but dir has no read access)

File Attributes

”Statuses” for files. Returns a “stat” struct with a bunch of info!todo it’s in 1 of our tutorial

Binary stuff yeyeyeye

00011000 << 2 = 001100000

Permission bits are a thing. st_mode stores that bitwise data. UGT is also stored

- U = set user ID, G = set group ID, T = sticky

For directories, set-gid means initial group of new file = directories group. Otherwise it’s the creator’s group.

Also sticky means others can’t delete/rename files. /tmp is the best example. You can create files, but only a select few can delete those files.

For exes, set-uid means “run with file owner privileges” and set-gid means “run with owner group privileges”

- This is how

sudoworks!

Low-level file IO

int open(const char *path, int flags);

- Takes in a file path as well as flags. Flags are bitwise. You have O_WRONLY, O_RONLY, etc.

- Returns a FD

- You can also specify the

mode. Like, you can haveO_CREAT.modehas the initial permissions (but those are restricted byumask) ssize_t read(int fd, void *buf, size_t count)- Returns how much stuff it read. Takes an FD. Outputs to buffer.

- Same with write. Yay

off_t lseekgoes to a certain offset/origin (the origin being SEEK_SET, SEEK_CUR, etc. etc.)- And of course,

int close(int fd)

umask sets the flags that mode will never receive

”Part of a process’s state” Returns the old state (to reset back to normal if you wanna!) That means the initial permissions for any succeeding “open”

fdopen opens a file via fd, but also exposes the char *mode arg to make life easy with those “r”, “w”, “w+”, modes

File Descriptors

0, 1, 2 are for stdio, stdout, and stderr

- Each process has a FD table

- The FD table has all open/dup FDs.

- They take up the lowest FD available. So after 0,1,2 is “3”!

- FD table is finite. Keep opening and you’ll run out

- The table maps entries to the system-wide “open file table”

- So when I was doing the epoll stuff, two processes might have the same the same “FD” number (5) but pointing to two files opened system-wide.

- Two OFT entries can refer to the same i-node

- Imagine two programs open a file and it goes to FD 3. Those two FD 3’s point to, idk open-file-table position 72. And that position points to i-node 43243 or something idk

- Two FD’s can refer to the same OFT entry via

dup- So

1and3can point to the same file, or perhaps even the terminal! Make3point to the terminal, and writing to it will write to the terminal. Confirmed!

- So

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

dup2(1, 32);

char *wa = "Hello world";

write(32, wa, sizeof("Hello world") - 1);

// Writes to STDOUT! Which is the terminal!

}Duplicating

int dup(int oldfd); returns a new FD.

dup2 dupes to specific entry number.

shell 2>&1

- stderr is being redirected to

1. - We can use

dup(1, 2)to do the same. Now,2points to the same file as1, which is the standard out terminal. - If I ever write into

2, it’ll write into the same file1is writing into. I FINALLY GET IT.

Processes and Redirection

Cloning your process

pid_t fork(void)

- This will clone most things. It runs the same code and at the same spot! (Right after

forkreturns!) - PID is the process ID (assigned at birth)

forkreturns0if it’s the child. Parent’s return is the PID of the child (which is non-zero, and not -1).- Anything else is an error therefore!

execlp(path, arg0, arg1, etc...., (char*) NULL)- Runs a program right then and there. Useful when you want to make the child process do exactly this.

- It doesn’t save code or data. Saves everything else (including FDs! However you can make them close by marking them as close on exec)

fork is the ONLY way to launch new processes. PID 1 is the “init” process launched by the kernel. It is the first. It has seen everything.

There are a bunch of processes-related commands. ps lists processes, top has a fancy UI

kill kills a process. pkill helps you out by searching like pgrep does.

Waiting for Godot Child

pid_t wait(int *wstatus);

- Waits for any child to terminate

wstatusreturns the child’s exit code or why it died- For a specific child, you use

waitpid. It also takesint optionslikeWNOHANGfor “don’t hand wait”.- Passing PID > 0 means you’re waiting for a specific child. For PID = -1 it’s for any child (returned)‘

wstatus

Complicated! There are many macros. They take “s” which is the status outputted

struct wstatus status;

if (WIFEXITED(status)) {

printf("Child exited!%d\n", WEXITSTATUS(status));

}

else if (WIFSIGNALED(status))

{

printf("Child was killed by signal: %d\n", WTERMSIG(status));

}

else if (WIFSTOPPED(status))

{

printf("Child was stopped by signal: %d\n", WSTOPSIG(status));

}If child dies and parent doesn’t call “wait”, and the parent is still running, we have a “zombie”. Kernel still has entry in process table for child, so it’s displayed at Z.

If the parent does and the child is still running, it’s orphaned! Kernel resets child’s parent to PID 1. Basically init adopts the child, lol.

If child dies, then init will call wait, so there is no zombie.

In the case where the child is a zombie, and then the parent finally dies, then the child’s parent becomes the kernel, who waits for the child and adopts it. Amazing. That’s the “combo move”

File Redirection

- What be redirection again? That’s when the output is sent from stdout to a file, right?

- It’s when you call a program whose result goes into another program

- The reason you need to

forkis because you call two programs at once. For instance, insort < infile, the child must callsortwithstdinbeing the inputtedinfile - Then we can continue our program!

- ==We NEED to fork, otherwise if we call

execlpour program will be replaced!==

- The reason you need to

Pipes

- They create a in-and-out relation. It returns the IN and OUT ends of the pipe. Since the file is shared by the child and parent processes, I can write into IN from the child and receive it in the parent. Auto opens everything, so make sure to close as well!

- It’s 1 way! Better than using a temporary file for complicated reasons I don’t want to explain

Pipe Hygiene

- Usually you use dup2 to make the read end point to stdin, or the write end point to stdout.

- Because of this you should ASAP close files you don’t need. ASAP!!! #todo This i will defo forget

Misc stuff

- If a writer keeps writing but the reader never reads, the kernel will keep buffering the unread data. If that runs out, then any

writecalls are blocked and hangs until the reader reads/closes the read end. - If the read end is closed, you have a Broken Pipe

- The process that’s writing receives a signal upon the write. By default it kills the process!

todo what is fcntl. Anyway you can use it to change a fd’s flags to use O_NONBLOCK which means read/write doesn’t block and just returns -1

Signals (>_>)

There are a bunch of them. It’s how the kernel communicates with processes for events/severe errors. They are a bunch of constants.

- SIGCHLD for instance, is called when a child dies/is suspected/resumed.

Signals are “pending” until delivered. A signal might pend for long if a process masks/blocks a signal — the event would pend until unmasked. There are many default actions for signals. Some can kill the program! Most are override-able, too and signal handler functions. All but SIGKILL (well obviously) Execution continues if signal ignored or handler returns normally. If not, syscalls fail with EINTR error

You can raise signals via raise(int sig)

sigaction() lets you change a certain signal’s sigaction (that consists of the sa_handler, SIG_DFL for default) and the sa_flags (0 for default)

sa_mask masks the signals that can happen when running handler. It’ll block these signals until the handler is done. By default, the signal being handled is automatically blocked.

If you want to override SIGPIPE (that’s the thing that happens when you write to a broken pipe) then you set the action to SIG_IGN (ignore). The process doesn’t die!

Within handler, we cannot call printf. Why? well since normal code could also be running printf. If during a printf call the signal is run, then it’ll be interrupted and mess up the middle of the call! This is especially bad since printf uses buffer/bookkeeping vars.

- TL;DR, don’t use

printf,fclose, orexit

If there are non-trivial things to do when a signal happens, do it outside of the handler. Make a global pipe. The handler will write to the pipe to notify normal code the signal has happened (you can write inside of handlers!)

The normal code will check the pipe. Now it’s safe to react and clean up.

Network sockets

- Server client relationship

- Unrelated processes can make contact!

- FDs are two-way streets. Pipes are 1-way.

Of the kinds of sockets, we have Unix domain (local to PC. Address is filename), IPv4 (over network, but loop back address for local). Has 32-bit address and 16-bit port number. IPv6 as a 128-bit address instead. Of those, there are “streams” and “datagrams”. Datagrams send data in packets. But they can be lost. Streams can restore data order though. We use streams.

For sockets, when we are creating a client (this is our receiver boy!)

- We create a “fd” via “socket”.

- We call connect (bind is for server).

- This means filling in the address struct.

- We use the fd to talk to the server

- And we close it when we’re done

For the server:

- We create an “sfd” via “socket”

- We bind it

- This means filling the address struct (again!)

- We call

listenwhich declares the sfd is waiting for clients to connect! - Now, we loop

- We accept(sfd). This returns a cfd. We communicate with this “cfd”

- Close sfd when we are done

Creating a socket

int socket(int family, int type, int protocol);

- type will be

SOCK_STREAMand family will beAF_INET - protocol is

0(we change for special circumstances)

Connecting

int connect(int fd, const struct sockaddr *server_addr, socklen_t addrlen);

- The first is the socket we created

- The second is the struct which we’ll go over in a sec

- The third is just the size of the

sockaddrwe use (it depends on IPv4 vs. IPv6. Sosockaddr_inis the way to go!)

IPv4 addresses!

127.0.0.1. This is the “readable” notation.

Big/Little Endian and presentation/network byte order

htonl()means “host to network long” andhtons()means “host to network short”- It does the conversion from machine to network

- To go to the other way, we use

ntohlandntohs. - Also to go from presentation to network byte order:

inet_ptonandinet_ntop

Bind

- Exact same as connect! Except this is for servers.

Listen and Accept

int listen(int fd, int backlog);- Max queue size of “backlong” (like, if there are guys tryna connect, it doesnt let more that 20 try at once)

- Returns -1 if error. 0 if success

- For

int accept(int fd, struct sockaddr *client_addr, socklen_t *addrlen);- This returns the client address and its size (opposite of connecting)

- I didn’t ever use the size though…

”No packet boundary”

When you write back to back, it takes time. So there’s the issue of the server reading a half-sent stream from your message. The write didn’t write everything! So it’s important to call read again to make sure you have everything you can get (i.e. the server is still readable).

- There are 4 scenarios for splitting/merging if the sender wrote several times when the receiver

- You might read part of word 1

- You might only read word 1

- You may read both wrods

- You may read word 1 and part of word 2

- See, those progressively read more! In local servers, it’s usually the second case (local servers are super super fast after all.)

Broken Pipe

- Make sure you set action via

sigaction(iirc) to ignore SIGPIPE via SIG_IGN! Then the process will not die and errno will be EPIPE

ITS THE FINAL SLIDE SHOW

da-na-naa naaaaa. Da-na-naa-naa naaasaa

- We need multiplexing to handle many clients at once, instead of waiting one by one for each client (that would be crazy!)

Using select()

int select(int n, fd_set *r, fd_set *w, fd_set *e, struct timeval *timeout);- Blocks until specified FDs are ready for read/write, timeout, or signal handled. Returns 0 if timeout, positive count if some FDs are aready, -1 if error or signal handled.

fd_set= holds a set of FDsn1 + highest FD to checkr= the FDs you want to read from. NULL if nonew= the FDs you wanna write frome= dw about it.timeout= max wait time. NULL for not needed- select() modifies the sets to report readiness!

This below example ONLY handles a simple case of reading from your stdin (pretending that is a client).

If you wanted more clients, you would have an array of fds, keep track of its size, and FD_SET those fds so that select knows to read them each time.

- Also instead of the simple if check to see if stdin is inside the “read”

fd_set, you would iterate over every item infd_set!

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <signal.h>

#include <sys/select.h>

// accessible from both signal handler and main

int pipefd[2];

void myhandler(int sig)

{

write(pipefd[1], &sig, sizeof(int));

}

int main(void)

{

fd_set readfds; // Constantly changing

struct sigaction myaction;

pipe(pipefd);

myaction.sa_handler = myhandler;

myaction.sa_flags = SA_RESTART;

sigfillset(&myaction.sa_mask);

sigaction(SIGINT, &myaction, NULL);

sigaction(SIGTERM, &myaction, NULL);

for (;;) {

FD_ZERO(&readfds);

// Monitors stdin and read-end of pipe

FD_SET(0, &readfds);

FD_SET(pipefd[0], &readfds);

printf("calling select\n");

// Because I installed signal handlers, select can return -1 after handled

// signals. No worries, just keep calling.

// Select will return when user types something, or when signal

while (select(pipefd[0]+1, &readfds, NULL, NULL, NULL) == -1) {}

// Now readfds has changed!

if (FD_ISSET(0, &readfds)) {

char line[1024];

// The client is ready to read!

if (fgets(line, 1023, stdin) != NULL) {

printf("user entered %s\n", line);

} else {

// But if it's ready, but nothing is read, that means the client has *closed*!

printf("user ends, bye!\n");

break;

}

}

if (FD_ISSET(pipefd[0], &readfds)) {

int s;

if (read(pipefd[0], &s, sizeof(int)) != -1) {

printf("received signal number %d. (No, I am not quitting!)\n", s);

// Exercise: If s==SIGTERM, quit, but quit with a HOWL!

}

}

}

return 0;

}- There are many functions for your

fd_set. - You ALWAYS have to set your

fd_set’s when calling select again, since select manipulates them.- Same with

timeoutstruct

- Same with

- ”Ready for read/write” can also be EOF, broken pipe, error, etc.

- ”ready for accept = ready to be ready”

- Means reading won’t block. BUt it might still block if another process beats you to reading, the write is so large it clogs the buffer again, or other weird scenarios.

Select limitations

- Caped at 1024 fd_set size

- When with many FDs (you look through them to FD_SET, and the kernel loops through them. Then you loop through them again to FD_ISSET)

- For linux, epoll is best

Epoll!

int epoll_create1(int flags)

- This creates an

epoll(for server)- Close it when you’re done

epoll_ctl(int epfd, int op, int fd, strut epoll_event *ev);- This adds/deletes/changes what to monitor

- The

epoll_eventspecifies what to look out for

int epoll_wait(int epfd, struct epoll_event *evs, int n, int timeout);- This waits until readiness, timeout, or signal handled.todo what does signal handling look like in this scenario?

epoll creation

epoll_create(int flags);The flag can be 0 or FD_CLOEXEC. It returns the epfd / epoll instance. Like normal FDs, you can close, dup, fork, etc. but it makes no sense to read/write into them.

epoll_ctl(int epfd, int op, int fd, struct epoll_event *ev)

- Returns 0 for success!

- Specifies what

fdto worry about reading/writing.- Usually

acceptwill give that FD to you. You then use it to callepoll_ctl. Whenever we write, an event will be had, so whenepoll_waitruns, it’ll append this very “control”

- Usually

- The OP can be EPOLL_CTL_ADD (monitor fd), EPOLL_CTL_DEL (DON’T monitor fd), or EPOLL_CTL_MOD (change what to monitor for fd)

- fd cannot be a regular file or directory, but it can be another epoll instance (😨)

ev= events to wait for (not used ifEPOLL_CTL_DELof course)

struct epoll_event

- The “events” field can be

EPOLLIN,EPOLLOUT,EPOLLONESHOT, orEPOLLET- These indicate ready to write, read, monitor only once, or edge-triggered (notify going from not-ready to ready ONLY)

- Level will make you read again and again when data arrives. Edge will not notify again.

- Then there’s the

datawhich is a whole other thing

typedef union epoll_data {

void *ptr;

int fd;

uint32_t u32;

uint64_t u64;

} epoll_data_t;- When you do

epoll_wait(), you get back what clients we are monitoring. The metadata is the same as what we set viaepoll_ctl - ITS A FLIPPING

UNION. HOW’D I NOT NOTICE THAT

epoll_wait(int epfd, struct epoll_event *evs, int n, int timeout)

evs is the array to recieve events. n is the array length. timouet is the milliseconds we timeout (or -1 if none)

Returns count of ready FDs (i.e. ow many entries in evs used)